文章目录

- 引入需求

- 代码原理解读

- s.chars()

- IntStream filter(IntPredicate predicate)

- long count()

- 补充:IntStream peek(IntConsumer action)

- 流操作和管道

引入需求

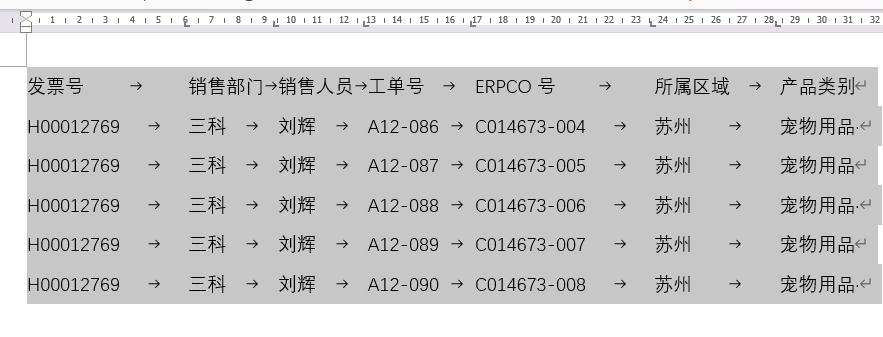

从一段代码引入

return s.length() - (int) s.chars().filter(c -> c == 'S').count();

其中 (int) s.chars().filter(c -> c == 'S').count(); 计算了字符串 s 中字符 ‘S’ 的数量。

下面解读其原理:

代码原理解读

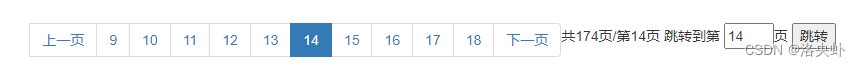

s.chars()

Java 中的 String 类的 chars() 方法是用来将字符串转换为 IntStream 的一种方法。IntStream是一个表示 int 值序列的流。

该方法不接受任何参数,返回一个 IntStream,其中每个元素是字符串中对应位置的 char 值。

String s = "Hello";

IntStream chars = s.chars();

chars.forEach(System.out::println);// 输出结果为

72

101

108

108

111

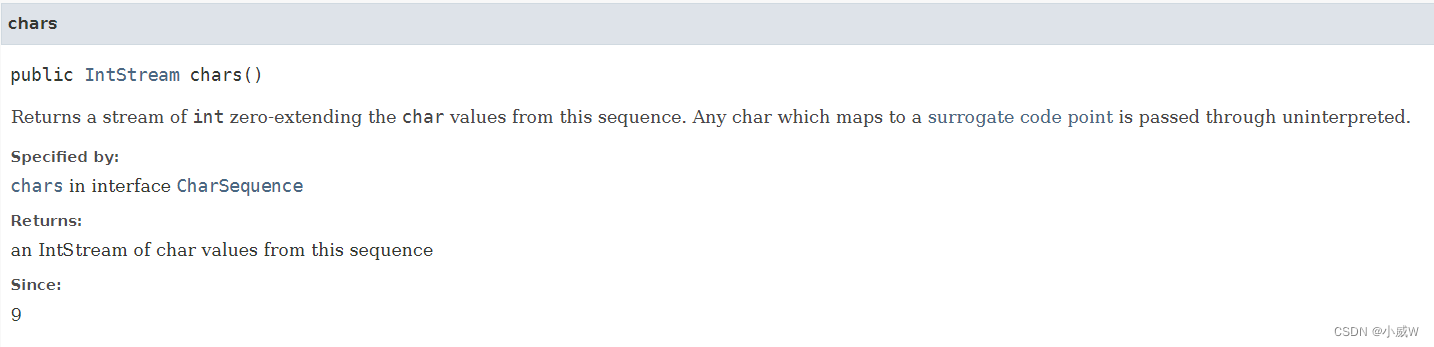

IntStream filter(IntPredicate predicate)

本题中使用的是 IntStream 类的 .filter() 方法 (除此之外其它类有的也会有 .filter() 方法)

Java 中的 .filter() 方法是一个中间操作,它会返回一个新的流,该流由该流中与给定 predicate 匹配的元素组成。(可以认为这是一个过滤器)

比如本题就是只保留了 c == 'S' 的元素。

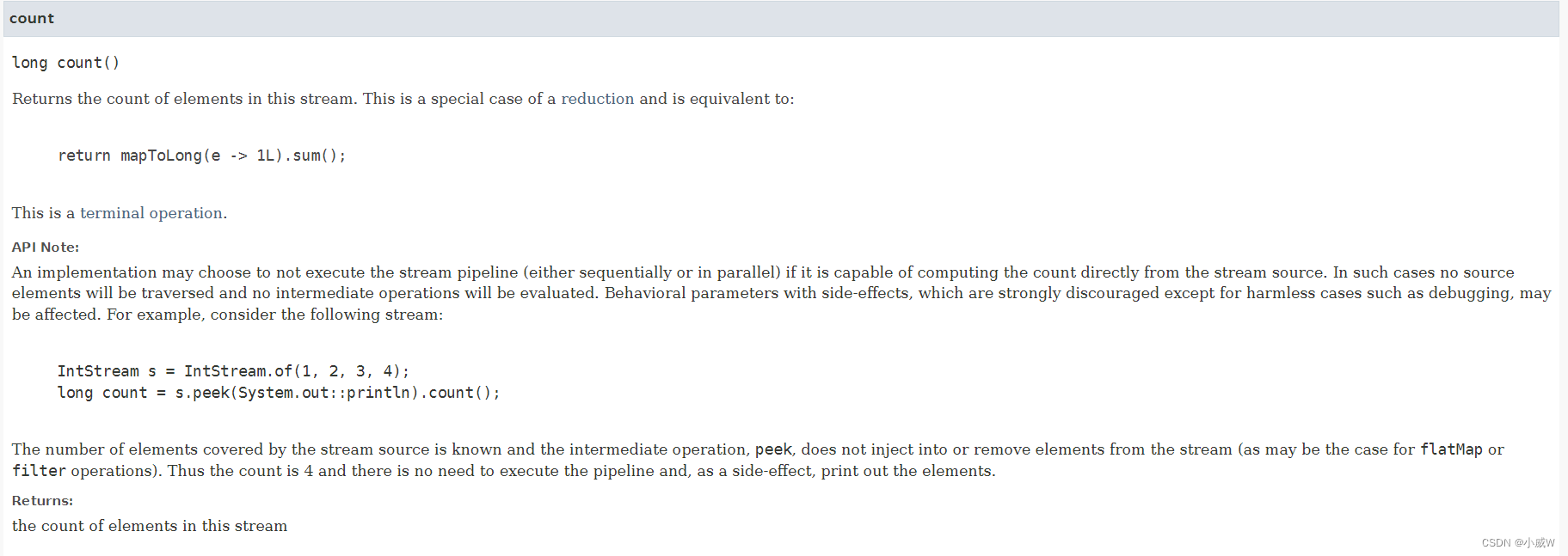

long count()

注意返回值是 long 基本数据类型。

Java 中的 .count() 方法是一个终端操作,它返回流中元素的数量。它是一种特殊的归约操作,它将一系列输入元素组合成一个单一的结果。例如,如果我们想要统计一个整数列表中有多少个偶数,我们可以这样写:

List<Integer> list = Arrays.asList(1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6); //整数列表

long count = list.stream() //创建一个流.filter(n -> n % 2 == 0) //根据谓词筛选出偶数.count(); //计算流中元素的数量

System.out.println(count); //输出结果 为 3

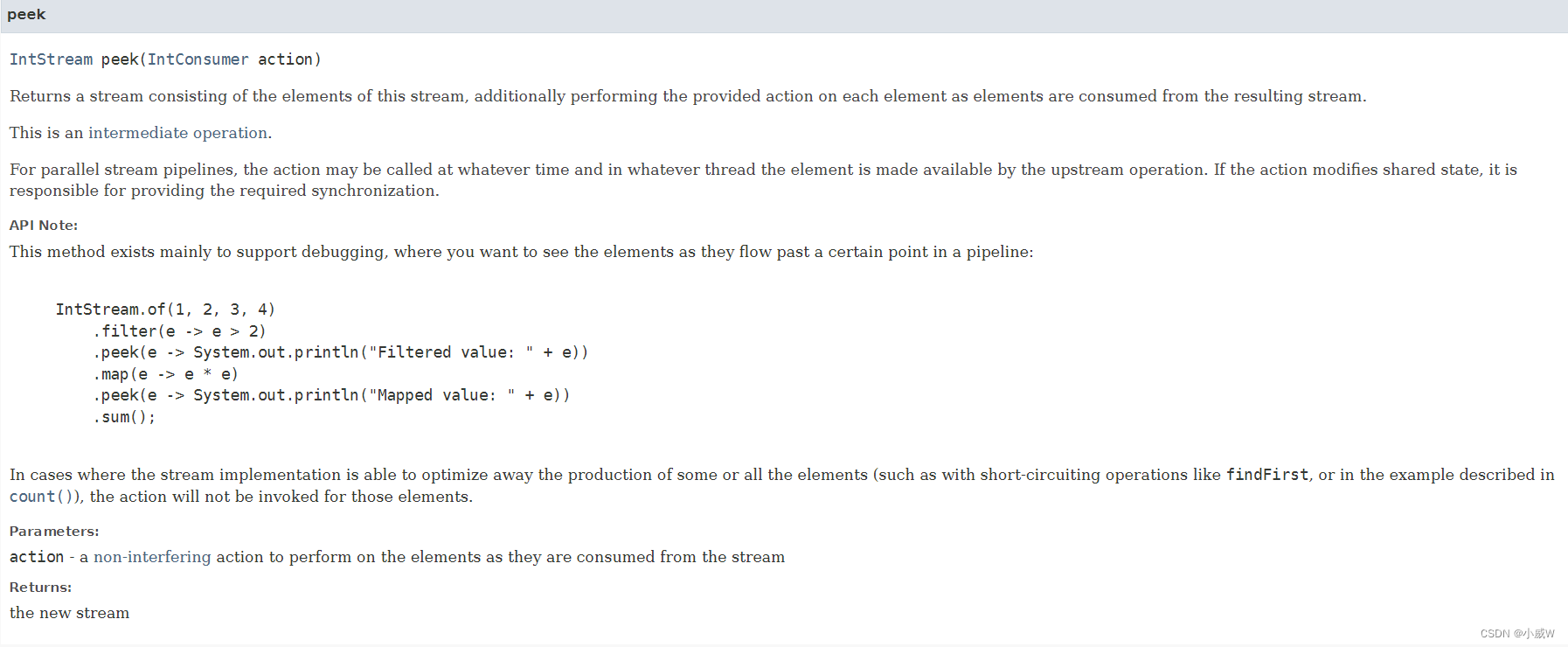

补充:IntStream peek(IntConsumer action)

https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javase/11/docs/api/java.base/java/util/stream/IntStream.html#peek(java.util.function.IntConsumer)

返回一个由该流的元素组成的流,并在从结果流中消耗元素时对每个元素执行所提供的操作。

此方法的存在主要是为了支持调试

即

peek() 方法不会改变流中元素的值或顺序,也不会影响流的终端操作。它只是在流中插入了一个额外的操作,用于观察或记录元素。它返回一个新的 IntStream 对象,因此可以和其他的中间操作或终端操作链式调用。

可以看下面的代码示例1:

IntStream.of(1, 2, 3, 4).filter(e -> e > 2).peek(e -> System.out.println("Filtered value: " + e)).map(e -> e * e).peek(e -> System.out.println("Mapped value: " + e)).sum();// 控制台输出结果为:

Filtered value: 3

Mapped value: 9

Filtered value: 4

Mapped value: 16

代码示例2:

IntStream.of(5, 3, 1, 4, 2) //创建一个整数流.peek(n -> System.out.println("Original: " + n)) //打印原始值.sorted() //排序.peek(n -> System.out.println("Sorted: " + n)) //打印排序后的值.sum(); //求和// 控制台输出结果为:

Original: 5

Original: 3

Original: 1

Original: 4

Original: 2

Sorted: 1

Sorted: 2

Sorted: 3

Sorted: 4

Sorted: 5

这时候会有疑问:为什么两段代码示例的控制台输出结果顺序好像不符合预期?

A:这是因为流的操作是惰性的,也就是说,只有当终端操作(如 sum() )需要时,才会真正执行中间操作(如 filter() , map() , peek() )。

因此,流中的每个元素都会按照管道中的顺序依次执行所有的中间操作,而不是先执行完一个中间操作再执行下一个。所以,在代码示例 1 中,对于第一个元素3,它会先被 filter() ,然后被 peek() ,然后被 map() ,然后再被 peek() ,最后才会被 sum() 。对于第二个元素4,它也会经历同样的过程。因此,Mapped value: 9 会输出在 Filtered value: 4 之前。

在上文中 count() 方法的文档中有这样一段代码:

IntStream s = IntStream.of(1, 2, 3, 4);

long count = s.peek(System.out::println).count();

这段代码对应着控制台没有任何输出,这是因为count() 方法是一个短路操作,也就是说,它不需要遍历所有的元素就可以得到结果。因此,对于一个有限的流, count() 方法会直接返回流中元素的数量,而不会触发任何中间操作(如 peek() )。这是 Java 9 中对 count() 方法的一个优化,以提高性能。

流操作和管道

Stream operations and pipelines

这部分的英文原文如下:

Stream operations are divided into intermediate and terminal operations, and are combined to form stream pipelines. A stream pipeline consists of a source (such as a Collection, an array, a generator function, or an I/O channel); followed by zero or more intermediate operations such as Stream.filter or Stream.map; and a terminal operation such as Stream.forEach or Stream.reduce.

Intermediate operations return a new stream. They are always lazy; executing an intermediate operation such as filter() does not actually perform any filtering, but instead creates a new stream that, when traversed, contains the elements of the initial stream that match the given predicate. Traversal of the pipeline source does not begin until the terminal operation of the pipeline is executed.

Terminal operations, such as Stream.forEach or IntStream.sum, may traverse the stream to produce a result or a side-effect. After the terminal operation is performed, the stream pipeline is considered consumed, and can no longer be used; if you need to traverse the same data source again, you must return to the data source to get a new stream. In almost all cases, terminal operations are eager, completing their traversal of the data source and processing of the pipeline before returning. Only the terminal operations iterator() and spliterator() are not; these are provided as an “escape hatch” to enable arbitrary client-controlled pipeline traversals in the event that the existing operations are not sufficient to the task.

Processing streams lazily allows for significant efficiencies; in a pipeline such as the filter-map-sum example above, filtering, mapping, and summing can be fused into a single pass on the data, with minimal intermediate state. Laziness also allows avoiding examining all the data when it is not necessary; for operations such as “find the first string longer than 1000 characters”, it is only necessary to examine just enough strings to find one that has the desired characteristics without examining all of the strings available from the source. (This behavior becomes even more important when the input stream is infinite and not merely large.)

Intermediate operations are further divided into stateless and stateful operations. Stateless operations, such as filter and map, retain no state from previously seen element when processing a new element – each element can be processed independently of operations on other elements. Stateful operations, such as distinct and sorted, may incorporate state from previously seen elements when processing new elements.

Stateful operations may need to process the entire input before producing a result. For example, one cannot produce any results from sorting a stream until one has seen all elements of the stream. As a result, under parallel computation, some pipelines containing stateful intermediate operations may require multiple passes on the data or may need to buffer significant data. Pipelines containing exclusively stateless intermediate operations can be processed in a single pass, whether sequential or parallel, with minimal data buffering.

Further, some operations are deemed short-circuiting operations. An intermediate operation is short-circuiting if, when presented with infinite input, it may produce a finite stream as a result. A terminal operation is short-circuiting if, when presented with infinite input, it may terminate in finite time. Having a short-circuiting operation in the pipeline is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for the processing of an infinite stream to terminate normally in finite time.

中文翻译如下:(这部分信息量很大很重要!)

流操作分为中间操作和终端操作,并结合起来形成流管道。流管道由一个源(例如Collection、数组、生成器函数或I/O通道)组成;然后是零个或多个中间操作,例如Stream.filter或Stream.map;以及诸如Stream.forEach或Stream.reduce之类的终端操作。

中间操作返回一个新流。他们总是懒惰;执行诸如filter()之类的中间操作实际上并不执行任何过滤,而是创建一个新流,当遍历该新流时,该新流包含与给定谓词匹配的初始流的元素。在执行管道的终端操作之前,管道源的遍历不会开始。

终端操作,如Stream.forEach或IntStream.sum,可能会遍历流以产生结果或副作用。在执行终端操作之后,流管道被认为已被消耗,并且不能再使用;如果需要再次遍历同一数据源,则必须返回到数据源以获得新的流。在几乎所有情况下,终端操作都很渴望,在返回之前完成对数据源的遍历和对管道的处理。只有终端操作迭代器()和拆分器()不是;这些是作为“逃生通道”提供的,以便在现有操作不足以完成任务的情况下,实现任意客户端控制的管道遍历。

懒散地处理流可以实现显著的效率;在像上面的filter map sum示例这样的流水线中,过滤、映射和求和可以被融合到数据的单个传递中,具有最小的中间状态。懒惰还可以避免在不必要的时候检查所有数据;对于诸如“查找长度超过1000个字符的第一个字符串”之类的操作,只需检查刚好足够的字符串即可找到具有所需特性的字符串,而无需检查源中所有可用的字符串。(当输入流是无限的而不仅仅是大的时,这种行为变得更加重要。)

中间操作进一步分为无状态操作和有状态操作。无状态操作,如filter和map,在处理新元素时不会保留以前看到的元素的状态——每个元素都可以独立于对其他元素的操作进行处理。在处理新元素时,有状态的操作(如distinct和sorted)可以合并以前看到的元素的状态。

有状态操作可能需要在生成结果之前处理整个输入。例如,在看到流的所有元素之前,对流进行排序无法产生任何结果。因此,在并行计算下,一些包含有状态中间操作的管道可能需要对数据进行多次传递,或者可能需要缓冲重要数据。包含完全无状态中间操作的管道可以在一次过程中处理,无论是顺序的还是并行的,只需最少的数据缓冲。

此外,一些操作被认为是短路操作。如果在无限输入的情况下,中间运算可能会产生有限的流,那么它就是短路。如果在无限输入的情况下,终端操作可能在有限时间内终止,则终端操作是短路。在管道中进行短路操作是处理无限流在有限时间内正常终止的必要条件,但不是充分条件。